TACKLING TOXIC POLLUTANTS

Carroll Courtenay // Southern Environmental Law Center // ccourtenay@selcva.org

Anna Killius // James River Association // akillius@thejamesriver.org

Joe Wood // Chesapeake Bay Foundation // jwood@cbf.org

Clean Water & Flood Resilience

Executive Summary

Industrial pollutants such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a threat to our environment and our health. These chemicals have been linked to cancer, infertility, and other serious impacts. Virginia needs to take steps to track and mitigate these toxic pollutants so that all communities benefit from clean water, clean air, and healthy soil.

Challenge

PFAS

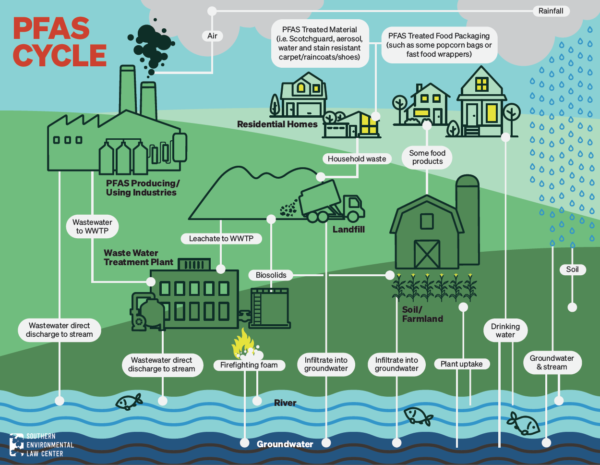

Commonly called “forever chemicals,” PFAS are toxic, bioaccumulative, and extremely persistent man-made chemicals.1 Exposure to these chemicals may impact fertility, raise cholesterol levels, and increase the risk of some forms of cancer.2,3 While the public can come into direct contact with PFAS through everyday items like waterproof and stain-resistant items, food packaging, and non-stick cookware, significant and concentrated streams of these chemicals can be released into our environment by firefighting foams, industrial uses, wastewater discharge, landfills, and land-applied biosolids.4 This can lead to contamination of drinking water, soil, crops, and forage for livestock and wildlife. Initial studies in Virginia have found PFAS contamination in public drinking water, private well-water, and in White Oak Swamp near Richmond International Airport, with additional studies on the way. 5,6,7

Unfortunately, Virginia does not require polluters to disclose or control these chemicals in their discharges or land-applied biosolids, leaving downstream communities, private well-owners, and farmers at risk or on-the-hook for the costly cleanup. Toxic facilities are more often concentrated in low-income communities and communities of color. One study found that members of these communities are more likely to live within five miles of a site contaminated by PFAS.8

Drinking water standards are an important component of protecting public health, but ultimately PFAS pollution must be stopped at its source. The Commonwealth should identify and control pathways of PFAS and put the responsibility on polluters—not communities—to clean up their waste by i) requiring polluters to disclose all chemicals released in their discharges and ii) including monitoring, reporting, and treatment requirements for PFAS in wastewater, solid waste, land-applied biosolids, and air regulations.

PAH-containing coal tar sealants

PAHs are carcinogenic compounds that are harmful to human health, wildlife, and creeks and rivers. Coal Tar Sealants, which are used on driveways and parking lots, have high levels of these toxic compounds. Studies have shown that residences adjacent to parking lots with coal-tar-based sealcoat have PAH concentrations in house dust that are 25 times higher than that of residences not adjacent to coal-tar-based parking lots.9 Young children (ages 0-6) are particularly vulnerable to health effects as they ingest high levels of house dust.

USGS research shows cancer risk is 38 times higher for people living adjacent to coal-tar-sealed pavement than for people living adjacent to unsealed pavement.

Recent studies also indicate significant negative impacts of PAHs on wildlife, including oysters, freshwater mussels, and various fish populations.10,11 Further, recent studies have demonstrated clear and immediate effects of coal tar sealant prohibition. Several cities and states around the country have already prohibited these substances. In one city, PAH concentrations declined by 58% within several years of a ban going into effect.12 Cost effective alternatives to these products exist and yet local governments in Virginia lack the authority to regulate these toxic substances.13 The Commonwealth should work towards phasing out these toxic products, and as a first step allow local governments to prohibit these substances in order to protect their citizens and local waterways.

Policy Recommendations

PFAS

Require industrial users to disclose and control all chemicals released in their discharges through Virginia’s wastewater permit and industrial pretreatment programs.

Fund DEQ and VDH to identify and eliminate potential pathways for PFAS contamination, which include wastewater discharges; land-applied biosolids; landfill leachate; air pollution; and food packaging.

Establish drinking water standards for PFAS and other toxic chemicals that fully protect public health.

Coal Tar Sealants

Provide a local option to regulate or prohibit coal tar sealants.

End Notes

1 “Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls,” Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (May 2021) https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp200.pdf.

2 Arlene Blum, Simona A. Balan, Martin Scheringer, Xenia Trier, Gretta Goldenman, Ian T. Cousins, Miriam Diamond, et al, “The Madrid Statement on Poly and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs),” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 no. 5 (May 1, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509934.

3 “Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls.”

4 “Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS,” US EPA (October 14, 2021). https://www.epa.gov/pfas/our-current-understanding-human-health-and-environmental-risks-pfas.

5 “Virginia Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Drinking Water Sample Study Summary,” Virginia Department of Health (September 30, 2021) https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/14/2021/09/VA-PFAS-Sample-Study-Summary.pdf.

6 “Henrico County finishes private well testing for potentially harmful chemicals,” NBC12 (March 5, 2022). https://www.nbc12.com/2022/03/05/henrico-county-finishes-private-well-testing-potentially-harmful-chemicals.

7 “Elevated PFAS Levels Found in the Chickahominy River Watershed,” Virginia Department of Health (October 28, 2021). https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/news/elevated-pfas-levels-found-in-the-chickahominy-river-watershed.

8 Genna Reed, “PFAS Contamination Is an Equity Issue, and President Trump’s EPA is Failing to Fix It,” Union of Concerned Scientists (October 30, 2019). https://blog.ucsusa.org/genna-reed/pfas-contamination-is-an-equity-issue-president-trumps-epa-is-failing-to-fix-it.

9 “Coal-Tar-Based Pavement Sealcoat—Potential Concerns for Human Health and Aquatic Life,” USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2016/3017/fs20163017.pdf.

10 Richard V. Lacouture, et al., “Susceptibility of eastern oyster early life stages to road surface polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs),” Repository & Open Science Access Portal (June 1, 2012). https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/24488.

11 “Understanding the Influence of Multiple Pollutant Stressors on the Decline of Freshwater Mussels in a Biodiversity Hotspot,” Science of The Total Environment 773 (June 15, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144757.

12 Peter C Van Metre, Barbara J Mahler, “PAH concentrations in lake sediment decline following ban on coal-tar-based pavement sealants in Austin, Texas,” Environ Sci Technol 48 no. 13 (July 1, 2014): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24930435.

13 “Alternatives for coal tar sealants,” Minnesota Stormwater Manual, https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Alternatives_for_coal_tar_sealants.