Reducing Plastics, Litter, & Marine Debris

Elly Boehmer Wilson // Environment Virginia // eboehmer@environmentvirginia.org

Zach Huntington // Clean Virginia Waterways // huntingtonza@longwood.edu

Clean Water & Flood Resilience

Executive Summary

Eradicating plastic pollution is a top priority for many Virginians. Smart policy can keep plastic waste out of Virginia’s streams, rivers, and coastal waters. Waters polluted with plastic have negative health effects on humans and wildlife. We can further tackle plastic pollution in Virginia by eliminating the most harmful types of mismanaged waste, incentivizing sustainable disposal of what we do use, and encouraging the shift to sustainable and reusable products. Virginia has made progress in eliminating plastic pollution in previous years and further actions would continue this legacy.

Challenge

Our society produces single-use plastic items that are discarded, creating pollution and further extraction of natural resources.1 When mismanaged, trash ends up in Virginia’s natural landscapes and waterways. The unintended consequences of single-use plastics result in devastating impacts on wildlife, including sea turtles, birds, fish, mammals, and important water-filtering bivalves like oysters and mussels through entanglement and ingestion.2

Up to 80% of debris in the oceans comes from land.

Up to eighty percent of debris in the oceans comes from land: mismanaged waste, litter, illegal dumping, and uncovered trucks (e.g., expanded polystyrene, food- and beverage-related items, cigarette butts, and plastic grocery bags).3,4 Studies show that mismanaged waste disproportionately affects historically disadvantaged and BIPOC communities.5 Exposure to plastic additives have negative biological effects on humans and wildlife6 with microplastics having been found in human lungs causing lesions and respiratory problems.7

In addition to on-land pollution sources, abandoned and derelict vessels (ADVs) obstruct navigational channels, cause harm to the environment, and diminish commercial and recreational activities. ADVs, most of which are plastic material reinforced with glass fibers, also have negative financial impacts.

While recycling is important, without collection mandates, robust reporting, and required benchmarks, it does not reduce single-use products nor does it hold producers responsible for the plastic pollution crises.

Solution

Eliminating Harmful Plastics

Low-quality, flimsy and single-use plastics such as foam, bags, and packaging are a challenge to manage due to their overabundance and material, both of which result in staggering amounts of mismanagement, unintentional litter, and plastic pollution. Eliminating the most harmful types of plastics through bans and reduction mandates is the best way to reduce pollution.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

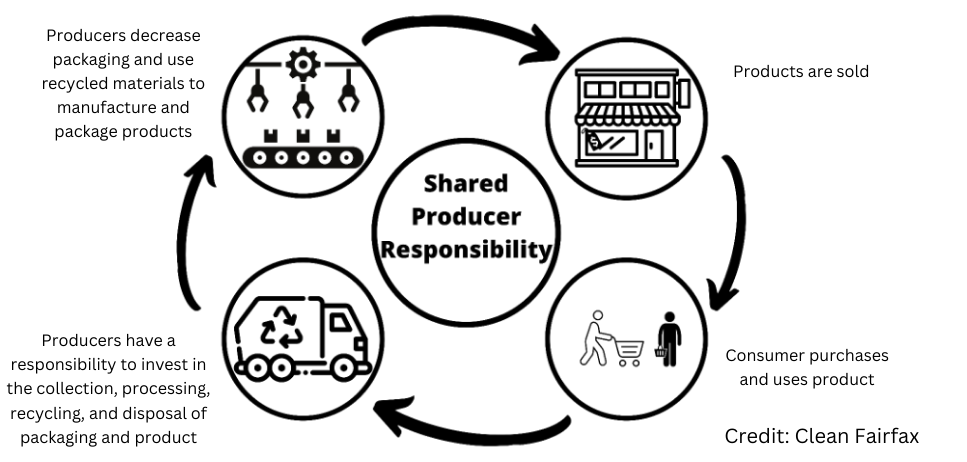

A producer responsibility program incentivizes and/or requires manufacturers to decrease packaging; increase recycled content; and create recyclable, reusable, or biodegradable products. Manufacturers are required to reduce waste and pay for recycling infrastructure, rather than taxpayers.

Closing the Waste Loop

While the primary goal of extended producer responsibility programs is to reduce the use of the most harmful single-use plastics at the source, these programs also work to close the waste loop by requiring producers rather than taxpayers to be financially and/or physically responsible for their products’ waste. One example of successful EPR is beverage deposit programs- Oregon’s program had an 88.5% bottle recycling rate in 2022.8 These programs best achieve waste reductions and high levels of recycling when they have strong collection mandates, benchmarks and reporting requirements.

Sharing responsibility between taxpayers/consumers and producers has these components:

Graphic description of shared producer responsibility program. Image Credit: Clean Fairfax

Cleaning up Plastic Pollution

Our goal is to reduce plastic pollution at the source, but we must clean up what ends up in our environment. Virginia’s Litter tax is one way this work is funded, but it generates the lowest revenue per capita of any state9– Virginia must implement policies to increase revenue in support of critical programs. The Commonwealth must continue funding programs that remove difficult marine debris such as fishing gear and abandoned and derelict vessels.

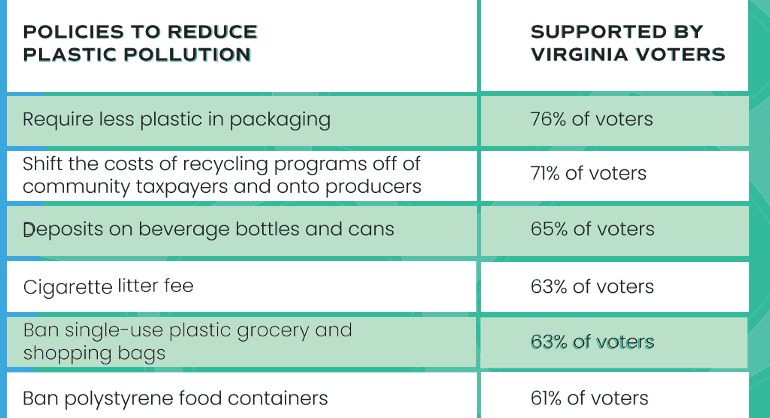

Policies to reduce plastic pollution supported by registered Virginia voters. Data adapted from Plastic Pollution: Virginia’s Voters Support Action: 2022 Public Perception Survey10

Policy Recommendations

Ban the use of single-use expanded polystyrene by food vendors by 2024 rather than a 7-year phase-out period.

Establish an Extended Producer Responsibility program in Virginia code focused on reducing harmful packaging.

Increase the litter tax to align with inflation and adjust the tax every five years.

$3 million for FY 2023-24 for the Virginia Abandoned and Derelict Vessel Prevention and Removal Program.

End Notes

1 United States EPA, Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery, Draft National Strategy to Prevent Plastic Pollution § (2023), https://www.epa.gov/circulareconomy/draft-national-strategy-prevent-plastic-pollution. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/documents/2016_and_2017_facts_and_figures_data_tables_0.pdf.

2 Ken Christensen. “Guess What’s Showing Up in Our Shellfish? One Word: Plastics.” National Public Radio (September 19, 2017). https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/09/19/551261222/guess-whats-showing-up-in-our-shellfish- one-word-plastics.

3 “2021-2025 Virginia Marine Debris Reduction Plan,” Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program (2021). https://www.deq.virginia.gov/our-programs/coastal-zone-management/coastal-conservation/marine-debris.

4 “Data from the 2021 International Coastal Cleanup in Virginia,” Clean Virginia Waterways of Longwood University. http://www.longwood.edu/cleanva/Data,ICCinVA.html.

5 “Neglected: Environmental Justice Impacts of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution,” United Nations Environment Programme (April, 2021). https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/35417/EJIPP.pdf.

6 Robert C. Hale et al., “A Global Perspective on Microplastics,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 125, no. 1 (January 6, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jc014719.

7 Kuo Lu et al., “Microplastics, Potential Threat to Patients with Lung Diseases,” Frontiers in Toxicology 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/ftox.2022.958414.

8 Monica Samayoa, “Oregon’s Bottle Bill Reaches Huge Milestone – More than 2 Billion Containers Redeemed in 2022,”(April 10, 2023). https://www.opb.org/article/2023/04/07/oregons-bottle-bill-reaches-huge-milestone-more-than-2-billion-containers-redeemed-in-2022.

9 Zach Huntington & Katie Register, “Opportunities to Reduce Plastic Pollution and Best Practices for the Virginia Litter Fund,” Report. Clean Virginia Waterways (June 2023). http://www.longwood.edu/cleanva/images/Litter%20Tax%20Report%202023.pdf.

10 L. McKay, K. Register, and S. Raabe, “Plastic Pollution: Virginia’s Voters Support Action: 2022 Public Perception Survey,” Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program (May, 2022). http://www.longwood.edu/cleanva/images/Survey_VA_Voters_Plastic_Pollution_Report_9-22-22_to_Media.pdf.